Warning: Outdated Content

This MP is from a previous version of CS 125. Click here to access the latest version.

MP0: Target Mode

Welcome to the machine project! As described in the syllabus, the MP gives you practice applying your skills to a large project similar to the ones you will work on in the future. In this way it nicely complements the practice you get on the much smaller and more contained homework problems.

So while much of this first checkpoint involves writing small pieces of code similar to recent homework problems, you’ll be integrating them into a large software project: a complete Android app. When you’re done the app will do something new and cool as the result of your efforts.

The overall machine project (MP) is broken down into individual checkpoints. We’ll refer to them like this: MP0 for the first checkpoint, or MP4 for the fifth checkpoint 1.

Also note that deadlines for each checkpoint vary based on your deadline group. MP checkpoint 0 (MP0) is due at:

-

8PM on Sunday 9/22/2019 for the Blue Group: all labs starting at 2PM or earlier (9, 10, 11AM, 12, 1, and 2PM)

-

8PM on Monday 9/23/2019 for the Orange Group: all labs starting at 3PM or later (3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8PM)

In addition, 10% of your grade on MP0 is for submitting code that earns at least 40 points by Sunday 9/15/2019 (Blue) or Monday 9/16/2019 (Orange). Late submissions will be subject to the MP late submission policy.

1. The Fall 2019 MP App: Campus Snake 125

We’ve provided some starter code for the machine project. But the app initially just displays a map. Over the course of the semester, you’ll work from this starting point to transform the app into a fun multiplayer game.

The game is inspired by Ingress, and represents a fusion of the virtual and real worlds enabled by ubiquitous powerful mobile computing devices—also known as smartphones. Teams compete to capture real-world objectives by visiting them before opposing teams. The objectives may be specific locations — target mode — or cells on an evenly spaced rectangular grid — area mode.

But there’s a twist: the snake rule. After a player has captured multiple objectives, the path between them forms a line. These paths are not allowed to intersect. Visiting a target will not claim it if doing so would add a line that crosses an existing line.

In target mode, the proximity threshold is how close a player must get to a target to capture it. Players and observers in a game are shown a map depicting claims and players' locations. A game creation screen allows specifying the objectives and inviting participants.

Feeling overwhelmed? That’s normal whenever you start a large project! Using the tools of the computer scientist, you can change the world, so of course it’s normal to feel a bit scared as you get started.

One of the objectives of the machine project this semester is to show you how to break down a big project into small pieces which you can complete one at a time. Make slow and steady progress over the next few months, and when you look back you’ll be amazed at what you created.

2. Learning Objectives

For MP0 you’ll turn the starter code into a single player version of a target mode game on some targets we’ve selected with a constant proximity threshold.

The core objectives of MP0 are both to keep you practicing writing simple functions and to get you started working with Android. Specifically, this checkpoint trains you to:

-

work with variables and arrays of appropriate types

-

perform simple operations on numeric values

-

use simple loops and conditional statements to process data in arrays

-

translate specifications into working code, and

-

work with test suites as part of your development process.

3. Assignment Structure

The machine project is a single Android app that you will continuously improve throughout the semester. Like all Android apps, it consists of Java code plus Android-specific resources.

Moderate-to-large software projects organize their code into multiple Java code files. You’ll typically only work with a few to complete each checkpoint. Some you won’t need to modify at all.

Most of the points on MP0 come from implementing well-defined Java functions like you’re starting to do on the homework. Connecting those to the game to make the app start to work takes less code, but you will need to spend some time looking over the code we’ve provided as you get oriented. We’ve included some helpful comments to summarize what’s going on and point you in the right direction.

While the comments in the files you need to work with should explain everything you need to know, you can also examine our official online documentation if you’re curious what each function and class does.

3.1. Android Studio Setup

Before starting the MP you must complete setting up Android Studio and have either an emulator or real device that you can run Android apps on. If you are struggling with this, please come to office hours for help—or post on the forum in the Android Studio category.

3.1.1. Install SDK version 28

The machine project uses the Android SDK (Software Development Kit) version 28. You install that using Android Studio as follows. You want to open the "SDK Manager". If you are at the welcome screen, click on "Configure" and the SDK Manager will be in the menu that opens. Otherwise, if you have a project open, SDK Manager is under the "Tools" menu.

Once you have the SDK Manager open, make sure that "Android 9.0 (Pie)" (API Level 28) is selected. If it is, you’re done! If not, click it to begin the installation.

3.1.2. Install the CS 125 plugin

Next, please download and install our CS 125 Android Studio Plugin. This will aid your MP development and provide us with valuable information as we continue to improve the course. You can read more about it here.

To install the plugin, first download it from the link above. Next, open the Android Studio plugin menu, select the gear icon, and choose "Install Plugin from Disk", and select the file you just downloaded.

3.2. Obtaining the MP

You’ll obtain the MP using GitHub—a very popular site that computer

scientists use to share their work.

So, first, if you don’t have one already,

sign up for a GitHub account.

Note that if you sign up with your @illinois.edu email address there are some

free goodies thrown in.

Next, use this GitHub Classroom link to create a copy of the repository containing the MP starter code. Once your repository has been created import it into Android Studio following our Git workflow guide.

At this point cool your jets for a minute while Android Studio finishes synchronizing and indexing your new project. Once that’s finished, double-check that everything is ready to go by opening the File menu and choosing Sync Project with Gradle Files.

Note that when you open the project in Android Studio you may receive a warning about "Gradle KTS Build Files." This is normal, and you can safely ignore this warning.

3.3. Your Goal

When you’ve finished Checkpoint 0, the app should display a marker on the map at each target’s position. When the user moves within the proximity threshold of a target and it can claimed without violating the snake rule, the target should turn green. Capturing a target should add a green line between it and the previously captured target—if it exists.

This sounds like a lot to do!

But you can enable these features by completing just three helper methods in

TargetVisitChecker.java:

-

getTargetWithinRange: identifies a target within the specified proximity threshold that hasn’t been claimed yet -

checkSnakeRule: determines whether a specified target can be claimed without violating the snake rule: that is, without creating a line that would cross an existing line between two previously claimed targets -

visitTarget: updates a path array to reflect that a specified target has been visited, returning the updated index of the array

When your helper functions are ready, you can use them to make the app do

something.

The Java file controlling the game/map screen is GameActivity.

You need to fill out two functions: setUpMap to place all the target markers

initially and updateLocation to react to user movements.

As noted in the comments inside those functions, some relevant variables are

declared and initialized for you near the top of the file.

Finally, LineCrossDetector, which already correctly determines whether two

lines cross, has some checkstyle issues that need to be corrected.

See the section on style later in this writeup.

4. Approaching MP0

Although the checkpoint may seem daunting at first, do not get discouraged! Focus on identifying what you need to do and understanding the requirements of each function, one at a time. There is really not a huge amount of code for you to write—our solution adds only several dozen lines, although yours may be slightly longer.

You have over two weeks to complete Checkpoint 0. Like programming in general, work at it at least a little every day and get help when you need it, and you’ll be amazed at what you can build.

4.1. Test-driven Development

We verify the correctness of your code on each checkpoint with a test suite, a

Java file containing code that exercises your code, comparing your results and

behavior to what we expect.

At first, the only test suite is Checkpoint0Test, though there are a lot of

other files to hold other code that supports the tests.

Each test suite contains several test functions, each of which tests one aspect

of your app.

For example, our testVisitTarget function verifies the correctness of your

visitTarget function.

You can use the test suites to perform iterative test-driven development. You should adhere to this approach as you work on MP0:

-

Start with one graded task that you need to accomplish—for example, implementing

getTargetWithinRange. -

Run the current checkpoint’s test suite, "Test Checkpoint 0," from the dropdown at the top near the green run button. Tests for parts you haven’t started working on yet should fail.

-

Begin working on the function. When you think you have a solution, re-run the test suite. You can run just one test by using a run button in the left margin of a test suite’s code.

-

If the test suite succeeds, you’re almost done—congratulations!

-

Make sure to run the full autograder to ensure you got all the points you expected. There are a few points for code style, described further below.

When a test suite fails, try to diagnose the problem by looking at what inputs caused your function’s behavior to diverge from what was expected. If your app produced incorrect results, the error will say what it expected. If your code crashed, the error message will show what problematic operation was attempted and what line of your code directly caused it. Either way, the error message also includes what line of the test suite was reached when the problem was hit. You’re not expected to fully understand the test suites, but reading their code may provide some clues about what’s going on in the case that your submission fails.

In general, the fewer lines of code you write before running a test, the better. This is not just a rule for beginners—experienced programmers spend a lot of time writing tests, in fact probably more than when they were learning. When you are starting out, it is easy to introduce bugs into your code. Bugs are easiest to catch one-by-one, and so the fewer lines of untested code, the more likely you are to identify errors in your logic or implementation.

If you receive a "no tests were found" error when trying to run the test suite, open the File menu and choose Sync Project with Gradle Files, then try again. If that doesn’t help, see the Troubleshooting Android Studio section below.

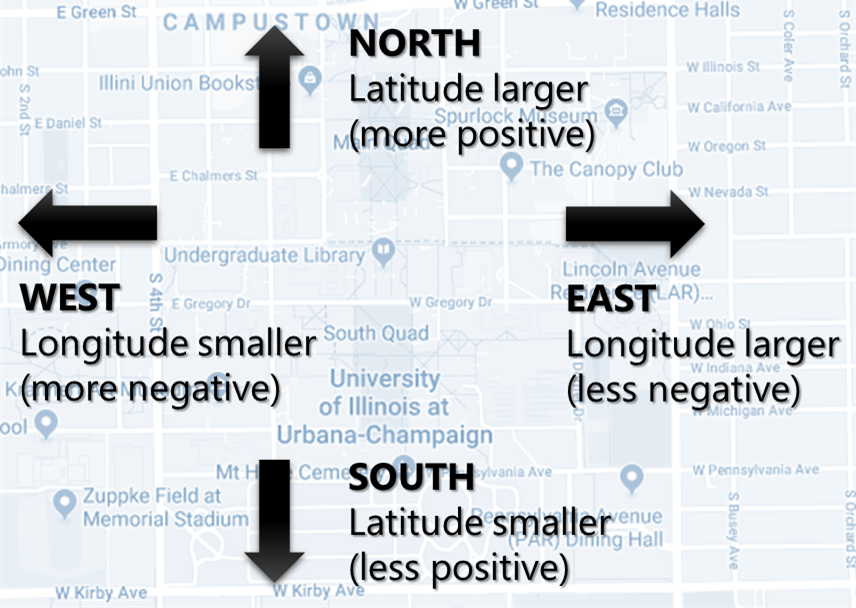

4.2. Understanding the Coordinate System

Since the app is a location-based game, it will be useful for you to understand location coordinates, especially when testing your app on a phone or emulator. Digitizing a position on the Earth turns a location into numbers that computers can manipulate, and is what gave rise to smartphone-based navigation, ride sharing, and is also enabling self-driving cars.

Locations are expressed as latitude-longitude (sometimes called "lat-long" or

LatLng) pairs.

You’ll often see them written as comma-separated coordinate pairs, longitude

first.

Latitude is defined relative to the Earth’s equator and specifies how far north or south you are. Longitude is defined relative to the Prime Meridian and specifies how far east or west you are. One increment of longitude is not the same physical distance as the same increment of latitude. The distance between adjacent meridians (a change of 1 in longitude) is different at different latitudes. At the small scales we’ll be working with, however, the curvature of the Earth can be ignored.

You may find this figure helpful:

4.3. Troubleshooting Your Code

There are several kinds of errors you may encounter as you work on the project. Distinguishing between them will help you fix them. Remember: programmers never stop making mistakes. They just get better at fixing them.

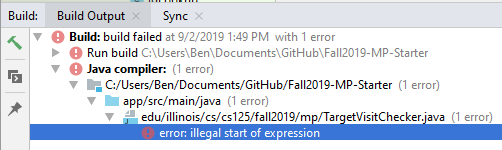

Before a program can be run, it must be compiled from your source code into something that can be executed. We’ll talk a bit more about this later in the semester. Problems in this stage are compile errors, indicating that your code has a mistake—often a syntax error—that makes Java unable to understand or permit what you’re trying to do. They’re flagged with red squiggles in the code editor or shown in a window like this:

You can usually double-click the error to jump to the code where Java identified the problem. However, unbalanced curly braces can make Java think the structure of your code is very different than you intended. If you suddenly receive tons of compile errors, look before the start of the problems to see if you have an extra or missing curly brace. This is one of many things that proper indentation helps with.

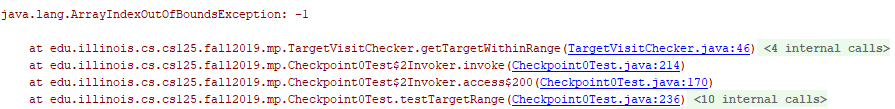

If compilation succeeds but the program tries to do something impossible or disallowed, that’s a crash—a runtime error. The test output pane marks the crashed test with a red icon and tells you went wrong and what line of code caused the crash. For example:

The first line states the problem, in this case that code tried to access the

out-of-bounds index -1 of an array.

What follows is called a stack trace.

The direct cause of the crash is at the top—in this case the

getTargetWithinRange method of TargetVisitChecker—and the rest of the

stack trace describes how your code reached this point.

Helpfully, the stack trace also includes the line number of the code that

crashed.

You can click the underlined link to jump right to that line.

The other lines are the chain of function calls that led to the crashing

function.

In this case, getTargetWithinRange was called by line 214 in

Checkpoint0Test’s `invoke function, which was called by an access$200

function attributed to line 170 2, which was called by line 236

of testTargetRange.

Usually you want to investigate the first stack trace entry that mentions your

code, but finding what the test suite was trying to check when your code crashed

may also provide some clues.

As you continue to write more complex code, stack traces will frequently lead

you from the place where the problem manifested itself to the real cause.

Finally, it’s common for code to cause no crashes but produce incorrect results. When these logic errors are detected, the test output pane marks the failed test with a yellow icon and displays a report similar to one from a crash. However, since your code finished executing but just returned a wrong result, only the test code which found the problem will be on the stack trace. Often the message will specify the expected (correct) value and the actual (your code’s incorrect) value. You can jump to the complaining line of the test suite to get more context and see what call(s) it made to your code.

4.4. Getting Help

The course staff is ready and willing to help you! If you need help, please come to office hours early and often, or post on the forum in the category we’ve created for MP0 questions. You should also feel free to help each other, as long as you do not violate the academic integrity requirements.

5. Troubleshooting Android Studio

Compiling Android apps is a complex process and several things can and will go wrong. If your app won’t compile or Android Studio seems to be misbehaving, try these fixes one at a time:

-

File | Sync Project with Gradle Files: This causes Android Studio to reexamine the numerous components of the project and often fixes "no tests were found" errors.

-

Restart Android Studio: Sometimes things just need to be turned off and back on again. Really.

-

File | Invalidate Caches / Restart: This will bring up a dialog with several options, from which you should choose "Invalidate and Restart" for the most complete refresh. However, note that Android Studio will busy itself after it restarts indexing your project.

-

Build | Rebuild Project: If there are errors in your code that are preventing it from compiling, this may bring up a useful list of them.

6. Android

Android is a Java-based framework for building smartphone apps that run on the Android platform. By learning how to build Android apps, your programs can have enormous impact. A couple years ago, Google estimated that there were 2 billion active Android devices. That’s over 25% of people on Earth—and several times more than iOS. And that number is certainly larger now.

However, Android is also a huge and complex system. It’s easy to feel lost when you are getting started. Our best advice is to just slow down, take a deep breath, and try to understand a bit of what is going on at a time. We’ll try to walk you through a few of the salient bits for MP0 below and in comments in the starter code. Google also maintains a great set of tutorials on beginning Android development.

Note that you will use Android for all of the MP this semester and for your final project, so put in some time to familiarize yourself with it now. It’s simply the best way to build exciting things—programs that you can share with your friends and family.

6.1. Logging

Like any other computer program, an important part of developing on Android is

figuring out what your program is doing by generating debugging output.

But there isn’t a console visible on Android devices for our familiar

System.out.println to write to.

However, Android has a simple yet powerful logging system.

Unlike System.out.println, logging systems allow you to specify multiple log

levels indicating the kind of output that you are generating.

For example, this allows you to separate debugging output that might only be

useful during initial development and a warning message that might indicate a

more serious problem or failure.

The Android logger also allows you to attach a String tag to each message to

separate them when you are debugging or developing.

So the final syntax of the call to generate a debugging message, for example, is

Log.d(TAG, message), where message is the text to log.

This assumes that the Java class you’re working in has a TAG constant defined,

which GameActivity does.

Logs are visible in the Logcat pane (near the bottom) of Android Studio.

You can type in that pane’s search text box to filter what messages you see.

For example, if your app crashed, filtering for FATAL will help you find the

crash details.

System.out.println will still technically work on Android; it just produces a

log message with

a tag of System.out.

It does have the advantage of showing up in the test results pane, but you lose

the ability to organize the logs by tag.

For more information, see Android’s official logging documentation.

Do you need to know this to complete MP0? Probably, since you need to determine what you app is doing or how things are going wrong.

6.2. `Activity`s and the Activity Lifecycle

Each Android Activity corresponds to a single screen that the user can

interact with.

For MP0 you’re only working with GameActivity, but the app contains several

that will be implemented or created in later checkpoints.

Most apps consist of multiple activities: maybe one for its dashboard, another

for a settings screen, and still others for other sections of the app.

There are a few important moments for an activity, especially when it is created and

when it is terminated.

Android provides functions that can be overridden (implemented) to handle

both of these events: onCreate and onDestroy.

It is typical for on onCreate method to perform tasks required to make the activity ready

for a user to use, such as configuring buttons and other UI elements.

For more information

review

Android’s

official Activity information.

Do you need to know this to complete MP0? No. But you may be confused by the overall app structure if you don’t review it.

6.3. Events

Why does code in your app run? In many cases it’s because new information has been made available, either by the user directly interacting with a control in the app or because another part of the system issuing a status update, like how our location listener service notifies the game activity of the user’s movements. Android components provide ways for an app to register handlers: functions that will be run when various events take place.

Our starter code registers one handler for when the map is ready for setup and another for when the GPS location has changed. Implementing them—making them actually do something—is up to you.

Do you need to know this to complete MP0? Yes! And it will be hard to understand how your app works without reviewing it.

7. Grading

MP0 is worth 100 points total, broken down as follows:

-

20 points for

getTargetWithinRange -

20 points for

checkSnakeRule -

20 points for

visitTarget -

20 points for making the single player target mode game work (by amending functions in

GameActivity) -

10 points for fixing all

checkstyleviolations -

10 points for submitting code that earns at least 40 points by 8 PM on your early deadline day

7.1. Test Cases

Automated testing is a hugely important part of modern software development. Just like computers are good at running programs, they are also good at running programs to debug other programs. Independently developing a method and the function that tests it allows the two to support each other. The test may find errors in the method, and the method may also identify errors in the test.

Testing simple Java functions is relatively straightforward: we invoke your code with some chosen inputs and compare the output to the known-correct result. Testing Android UIs, however, is more difficult. This semester we will continue using Robolectric to test your app code in a Java environment that simulates Android.

For the first checkpoint we test each of the three helper functions with some

simple manually designed test cases, then exhaustive test cases using many

randomly generated inputs.

Since each test function stops as soon as it detects a problem, we placed the

simple cases first so you can use them during iterative development.

In particular, some simple cases in testSnakeRule have diagrams that visually

show why the expected answer is correct.

7.2. Autograding

We have provided you with a local autograder that you can use to estimate your current grade on your own machine as often as you want. Your Android Studio project contains a run configuration called "Grade" that will run the autograder for the current checkpoint. You can also run the grader by installing our plugin and then pressing the button that looks like the CS 125 shield.

Before your grade your checkpoint you will need to identify yourself by entering

your @illinois.edu email address into the email.txt file located in the root

project directory.

The autograder will not run until you do this.

Please make sure to get this right!

If you don’t, your results will not be visible on the grading page, and may be

attributed to another student—putting you at risk of an academic integrity

violation.

Unless you have modified the test suite or autograder configuration, the autograding output should approximate the score that you will earn when you submit. If you modify our test cases or the autograding configuration, all bets are off. You may also lose points if your solution runs too slowly and exceeds the testing timeouts.

7.3. Submitting Your Work

Note that official MP grading for Fall 2019 is not working yet. You can still score and grade your assignment using Android Studio, but no official grades will appear on our grading page after you submit. We notify you when official grading is available.

First make sure you’ve identified yourself in your repository by entering your Illinois

email address into the email.txt file in the outermost folder of the project.

Whenever you make progress you want to save, you should be making a Git commit (VCS | Commit). Commits only exist on your computer until you push them (VCS | Git | Push). Every time you push your MP, we grade the checkpoint you’re currently working on. Official autograding takes just a few minutes, then you’ll be able to see results on the MP grade page.

7.4. Style Points

Most of the points on each checkpoint are for correctly implementing the required functions. The other 10 points are for style. Writing readable code according to a style guideline is extremely important, and we are going to help you get into this habit right from the start. All software development companies and most active open-source projects maintain style guidelines. Adhering to them will help others understand and integrate your contributions.

We have configured the checkstyle plugin to enforce a variant of the

Sun coding style.

Android Studio should naturally produce formatting that meets this standard.

So you shouldn’t have to fight with it too much to avoid checkstyle violations.

For ease of finding style problems, Android Studio flags them with red squiggles

under code and with red tick marks on the scrollbar.

You can hover your mouse over such indicators to get more details on what

checkstyle is complaining about.

You will also get a full list of checkstyle errors at the top of the grading

output.

You may find these requirements a bit annoying at first, but we trust that you will get used to them. Once you build good style habits, you won’t have to think about them anymore, and will just go on writing beautiful code.

8. Cliffhanger

After completing MP0 you may be thinking that dealing with locations as multiple arrays is unwieldy. You’re right! You’ll soon learn a better way to handle pieces of related data, and in a future checkpoint you’ll revisit the code you wrote here to apply that technique. And of course there are plenty of other new features to implement, like area mode which we’ll tackle next checkpoint.

8.1. Complete App Demo

If you can’t wait to see how the app will work when you’re done with the MP, you

can set our module manager to use all of our provided libraries.

There’s a file called grade.yaml in the root of the project that will be used

in later checkpoints to indicate what you’re currently working on, but if you

change its checkpoint setting from 0 to demo and its useProvided setting

from false to true then do File | Sync Project with Gradle Files, building

and running the app will produce our solution.

(The Gradle sync step is important! Without that, very strange behavior will

occur.)

Make sure to change those settings back and Gradle sync again before trying to

grade or submit, since you don’t get points for grading our known good solution.

9. Cheating

Please review the CS 125 cheating policies.

All submitted MP source code will be checked by automated plagiarism detection software. Cheaters will receive stiff penalties—the hard-working students in the class that are willing to struggle honestly for their grade demand it.