Generics

> Click or hit Control-Enter to run Example.main above

Review: Remember Arrays?

int[] numbers = new int[] {5, 6, 7};

System.out.println(numbers[0]);

numbers[1] = 8;-

Arrays map an index (0, 1, 2,

array.lengthto a value). -

The value can be anything, but the indices had to be be integers.

-

No longer!

Review: Java Maps

A Java Map allows us to use any object like an array index.

import java.util.Map;

import java.util.HashMap;

Map<String, Integer> stringValues = new HashMap<>();

stringLengths.put("test", 5);

System.out.println(stringLengths.get("test")); // Prints 5

stringLengths.put("test", 7);

System.out.println(stringLengths.get("test")); // Prints 7Brief Map Implementation

So how do we implement a Map?

-

Use a

hashCodeto retrieve a hash code for each object. -

Use that value—or a smaller part of it—as an index into an array.

-

But what about collisions?

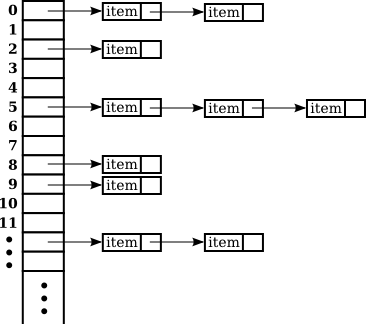

Map As Array + Linked List

> Click or hit Control-Enter to run Example.main above

HashMap Performance

Let’s consider the performance of our simple HashMap in two cases. First, if

the array is very small relative to the number of items:

-

put: O(n) with n being the number of items -

get: O(n) with n being the number of items -

At this point the

HashMapis acting like a linked list.

HashMap Performance

Let’s consider the performance of our simple HashMap in two cases. Second, if

the array is very large relative to the number of items:

-

put: O(1) -

get: O(1) -

At this point the

HashMapis acting like an array. -

What’s the problem? It requires a lot of space.

Realistic HashMap Performance

In reality we want our HashMap to blend the good features of an array and a

linked list.

-

Usually implementations will enlarge the array part of a

HashMaponce it gets filled past a certain point (called the load factor).

Looking forward to CS 225 yet?

This is cool stuff!

Cryptographic Hash Function

Hash functions already provide:

-

Determinism: it can convert an arbitrary amount of data into a single limited-size value. If we repeat the computation on the same data, we get the same value.

-

Uniformity: over many inputs, each output value is equally likely.

-

Efficiency: it is efficient to compute.

But what if there were hash functions with the following new properties:

-

Given the hash, it is infeasible to determine the original input

-

A small change to the input produces a large change in the output

-

The function is difficult to compute, not easy

Cryptographic Hash Functions

A hash function that satisfies these properties is known as a cryptographic hash function, largely because they are ubiquitous in modern cryptography.

A Simple Example

I need to be able to check your password, but I don’t want to save it. Is that possible?

-

Yes!

-

Save the cryptographic hash of your password, not the password itself.

-

When you submit your password, I hash it and compare it with the saved hash.

-

If someone steals my database, they can’t recover the original passwords.

-

Given the hashes, you can’t recover the original passwords

-

Hash values reveal nothing about how close you are to the actual password

-

Hashing inputs to test them is expensive

-

Another Example

Heard of blockchain?

Blocks are linked through cryptographic hashes. And the blockchain is secured through an old idea called Hashcash.

-

Given a hash value of a given size, I can estimate how much work you’ll have to do to guess the input that produced that value

-

So I can force you to do that work and verify that you did it easily by hashing the value that you gave me

Hashcash Example

-

Alice: "Here’s a challenge for you Bob, find an input that produces hash

39c3aa4015e7964914c311915316a2f78157c946. -

Bob: "Geez, that’s hard. Give me a few minutes… OK, got it."

-

Alice: "Wow, you’re right. I computed the hash and it’s

39c3aa4015e7964914c311915316a2f78157c946that must have been hard."

Blockchain Proof of Work

And, Beautiful Theory

In computer science, a one-way function is a function that is easy to compute on every input, but hard to invert given the function’s output for a random input.

The existence of such one-way functions is still an open conjecture. In fact, their existence would prove that the complexity classes P and NP are not equal, thus resolving the foremost unsolved question of theoretical computer science.

Questions About Hashing?

Java Generics

Lists and maps are the two data structures you meet in heaven. Together you can use them to solve almost any problem.

But you’ll usually use Java`s built-in implementations.

import java.util.List;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.LinkedList;

import java.util.Map;

import java.util.HashMap;

import java.util.TreeMap;

List list = new ArrayList();

List anotherList = new LinkedList();

Map map = new HashMap();

Map anotherMap = new TreeMap();> Click or hit Control-Enter to run Example.main above

Compiler Errors v. Runtime Errors

Java and many languages that followed it have tried to transform runtime errors into compiler errors. Why?

-

You compile your code before it runs: and so before you have to demo it to a client, or before you deploy it to hundreds of users.

-

Catching errors at this stage is critical.

Generics

Java generics allow us to create reusable classes while allowing the compiler to check our code for correctness.

Type parameters tell the compiler what we are going to do with each data structure.

import java.util.List;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.Map;

import java.util.HashMap;

List<Integer> integerlist = new ArrayList<>(); // This is list of Integers

Map<Integer, String> = new HashMap<>(); // This maps Integers to StringsGeneric Rationale

Java generics allow to combine two desirable features of the language:

-

Polymorphism: because every object inherits from

Objectit is easy to build general purpose data structures that can operate on every Java object -

Type Checking: however, upcasting everything to

Objectmakes it impossible for the compiler to perform compile-time type checking -

Generics are intended to allow us to have the best of both worlds

> Click or hit Control-Enter to run Example.main above

Generifying Your Classes

So we know how to use existing generic class. But how do we provide our own?

Class Type Parameters

First, we have to declare our class to accept type parameters:

// T is a type parameter that can be used throughout our class

public class SimpleLinkedList<E> {

// get returns a reference of type E

public E get(int index) {

}

// set takes a reference of type T as its second argument

public void set(int index, E value) {

}

}Parameters Are Not Variables

Class parameters are not variables.

I can use them where I would normally provide a type, but I can’t get or set their values.

public class SimpleLinkedList<E> {

// I can use the parameter here as a return type...

public E get(int index) {

E = String; // But I can't do something like this

}

}Compiling Generic Classes

To help understand how generics work you can imagine the compiler rewriting them when it compiles your code.

Original and Rewritten List

public class List<E> {

public E get(int i) {

}

public void set(int i, E value) {

}

}

List<String> list = new List<>();public class List {

public String get(int i) {

}

public void set(int i, String value) {

}

}

List list = new List<>();Original and Rewritten List

public class List<E> {

public E get(int i) {

}

public void set(int i, E value) {

}

}

List<Integer> list = new List<>();public class List {

public Integer get(int i) {

}

public void set(int i, Integer value) {

}

}

List list = new List<>();Type Erasure

Note that this is not actually what happens.

-

The compiler only creates one instance of each generic class

-

Type information is used during compilation to check access but then erased

-

But this isn’t a bad mental model of how generics work in practice

Multiple Type Parameters

Classes can use one or several type parameters:

// This is a generic list storing elements of type T

public class SimpleLinkedList<T> { }

// This is a generic map mapping elements of type K to type V

public class SimpleMap<K,V> { }Parameter Naming Conventions

To avoid confusing type parameters with variable names or other keywords, Java has established conventions for naming them.

-

By convention type names are single uppercase letters:

T,K,V,E, etc. -

Note that this is just a convention: it’s not enforced by the compiler

-

Certain type parameters have conventional meanings:

-

Efor element (which we’ll use for our lists) -

Kfor key andVfor value, (which we’ll use for our maps) -

Nfor a number

-

Original and Rewritten Map

public class Map<K, V> {

public V get(K key) {

}

public void put(K key, V val) {

}

}

Map<String, Double> map = new Map<>();public class Map {

public Double get(String key) {

}

public void put(String key, Double val) {

}

}

Map map = new Map();Original and Rewritten Map

public class Map<K, V> {

public V get(K key) {

}

public void put(K key, V val) {

}

}

Map<Integer, String> map = new Map<>();public class Map {

public String get(Integer key) {

}

public void put(Integer key, String val) {

}

}

Map map = new Map();> Click or hit Control-Enter to run Example.main above

Questions About Generics?

Midterm 2

The third and final midterm will be held next Monday.

-

The focus is data structures and algorithms, but completing the programming questions will require both imperative and object-oriented programming

-

There are three programming problems together worth 50 points. Most have partial credit.

-

Our final midterm represents your more sophisticated set of programming tasks yet.

Midterm 2 Problems

As always, the best way to review for the midterm is to review the practice homework problems.

Midterm 2 includes three programming tasks:

-

One question on lists that is very similar to a homework problem

-

One question on trees that is very similar to a homework problem

-

One question on sorting that is directly drawn from the homework

Next Few Classes

-

Friday: more about generics.

-

Monday: midterm exam (no class).

-

Wednesday: wrap up.